I have decided to inaugurate a new setting, grounded in the history and folklore of the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region. I won't deny that part of the inspiration came from Al-Qadim (like part of the inspiration for Kadmeian Mysteries came from Mythic Odysseys of Theros). But I don't think 'official' settings do historical fantasy that well - there is a fear of them, because our history contains too many 'disturbing' elements. So be it.

Overview

Over six centuries ago, the Apostle received the last Divine Revelation, closing the epoch of the prophets. Since that time, his followers among the Thani people, armed with the Taweeth - - the full record of the Incantation he heard - have spread far and wide, to the very ends of the earth. The realm they built lies at the very center of the ecumene - it is the al-Alam al-Wasat - the Middle World. All but the wildest and most wretched of beings know of and pay homage to the Apostle's vicar - the Caliph - who rules in wisdom and justice as befits the Shadow of God on Earth. From within the Garden of Virtue in the great city of Shahrinoor, the Caliph commands the Faithful, guiding them toward the fulfillment of God's commandments. In recognition of his power and piety, creatures from the four corners of the world flock to Shahrinoor and other great cities of the realm to worship in the golden-domed Houses of Prostration, to marvel at the wonders from across the world sold at the great souks, and to realize themselves in one of the myriad trades plied in the Caliph's domains. All the most important caravan routes - the Way of Silk, the Way of Spice, the Way of Gold, the Way of Slaves, and the Way of Pearls - converge on the capital. The workshops of the great cities produce the world's finest and most wondrous wares - swords that never dull, carpets rumored to be able to fly, and multicolored glass vessels that can contain jinn. Stalls and private collections teem with all manner of books - even ancient, obscure, and cursed ones, while the sages toiling away at the Bait al-Hikhmah and other houses of learning produce ever more volumes. All manner of humans and other rational creatures - jinnasi, shaytani, the angelic aasimun, the goliaths of the House of Aad, and even the rukhani - avian offspring of Rocs or perhaps the Anqa - rub elbows with one another in the streets of the Caliphate's great cities.

|

| The Middle World, in a galaxy far away |

But be not seduced, Believers, by tales of the Caliphate's greatness. For behind its brilliant façade, the fabric of the Middle World has begun to grow thin. Centuries of soft living in the cities have seen the nomadic spirit of righteousness, nobility and solidarity that spread the Khudi faith to the four corners of the world. Many great lords and officials became overcome with pride, counting the blessings God bestowed on the Caliphate as their own achievements. Some became so covetous as to carve out their own kingdoms within the realm, maintaining loyalty to the Caliph in name only. Some were overcome with jealousy, and turned on their neighbors. One in particular - a sectarian who later became known as the Old Man of the Mountain attracted a corps of stealthy and fanatical killers to dispense with any who opposed him. With time, they began to simply assassinate people for money. All this discord and dissension did not go unnoticed by outsiders. The barbaric Fargun from the north began to raid coastal areas of the Caliphate, and even took several important towns, slaughtering all the inhabitants. But a far greater danger stirred in the East. Some travelers reported that the seals imprisoning the tribes of Juj and Majuj were removed, causing fierce and bloodthirsty warriors to pour through the breach in great numbers. A comet appearing in the sky that year was interpreted by some sages at the Bait al-Hikmah to signal the coming destruction of the caliphate. As some sages began to proclaim that the devastation by Juj and Majuj were prompted by God's wrath, and called for returning to the original faith of the Apostle, news of zealots who styled themselves Mahdi - restorers of justice and righteousness in the End Times - began to reach the capital from various corners of the Caliphate. Refugees from the regions engulfed by Juj and Majuj hordes streamed westward to find sanctuary, while merchants sought to reroute caravans and trading ships to avoid economic route. Cemeteries from abandoned settlements reportedly teemed with ghûl, causing travelers to stay away, Throughout the Middle World, people and all rational creatures started asking whether the glorious destiny they had taken for granted had become disrupted by their own lack of faith. For God sees all things.

When adversity touches humans, many turn their eyes toward God. Sensing that perhaps the End was near, many people redoubled attempts to live a pious life - praying consistently, giving alms, fasting, and going on pilgrimages despite increased risks. Some sought salvation by taking up the sword against the Juj, Majuj, Fargun, and other infidels, and to recover initiative by extending the purview of the Khudi faith. Some turned instead to seek a more private and intimate knowledge, as the Community of the Faithful had become disrupted. Others still chose more selfish pursuits, such as the garnering of what wealth they could, by any means at their disposal. Opportunities arose to explore distant regions and mysterious islands in the Bahr al-Fayruz, where frightful serpents and monstrous birds such as the Rocs were reported. Others raided tombs built long ago in the Age of Ignorance, for armies of sorcerers sought to fill a growing demand for manufactured talismans, scrolls, and potions. Others hired adventurers to seek out the ancient abode of a race of giants called Irem - the City of Pillars - and to uncover it from beneath the sands. Wiser sages suspected that the cause of all the trouble lay with the jinn - creatures made of smokeless fire who lived in the Alam al-Ghayb - the Invisible World - and have simply waited for an opportunity to sway people from the Path of Righteousness and to ensnare them in their schemes. Items purportedly allowing wielders to command the jinn were found with increasing frequencies, though they typically led the latter toward perdition. But none captured the imagination as much as the Seal of Tabitha - an ancient relic that allowed its wielder to command the jinn with God's sanction. The ring that bears this seal is unfortunately lost, but it is now sought by a variety of creatures with increasing urgency.

Religion

Religion is the most important aspect of al-Alam al-Wasat, the spirit that animates it. The dominant religion of the Caliphate, shared by at least 4 out of 5 of its residents, is called al-Khud, and its adherents are the Khudi. The Khudi worship a single God whom they call al-Wakim. Through the agency of an angel called Karim, al-Wakim revealed himself to a man called Baha, and bade him to incant the revelation he spoke unto him. In later years, the Taweeth (or Incantation) memorized by Baha and his followers was written down. It is regarded as the literal word God, which cannot be altered, explained away, or even translated. It is also regarded as the last revelation to God's creatures, with which the prophetic age closes. Baha is venerated as the last prophet and Apostle by the Khudis, though is not at all seen as divine, rather a human who is worthy of emulation in all things. Al-Khud is strictly monotheistic, regarding all other gods as figments of the imagination and products of ignorance, or deceits perpetrated by jinn, who, like humans, are naught but God's creatures.

_who_came_to_m_-_(MeisterDrucke-972044).jpg) |

| Receiving the Revelation |

The fundamentals of al-Khud are easy to grasp for any potential convert. One is to profess faith in al-Wakim, and accept Baha as His Apostle. One is to pray five times a day. One is to give alms to the poor. One is to fast on appropriate holidays. And one is to go on pilgrimage at least once in their life, especially to the site of the Salb - a black substance fallen from heaven, where al-Khud got its start under Baha's leadership. As being the last revelation, al-Khud is necessarily universal, and the Khudi are generally encouraged to expand the boundaries of the faith by both peaceful and warlike means.

Al-Khud as a whole lacks a single hierarchical priesthood. Rather, proper belief and proper practice is dictated by the Taweeth and authoritative traditions stemming from the Apostle. Beyond that, orthodoxy and orthopraxy is determined by authoritative scholars and jurists belonging to the community of the learned - the ulama.There are several schools of thought that are regarded as authoritative, and though they agree on the fundamentals, their interpretations differ on the finer points, on which each of the established schools issue distinct opinions.

The community of jurists determine the practice of al-Khud for the majority of the Faithful. They also select local prayer leaders (imams) and judges (qadis). Similarly, in the early years, a council of jurists would gather to select the leader of the whole community of the faithful - the umma, known as the Caliph. In later times, the council would typically simply approve the accession of one of the previous Caliph's children or relatives. Though religion and politics are closely intertwined in al-Khud, the Caliph is primarily a secular ruler, while spiritual authority lies mostly with the top jurists and judges.

Though as the final revealed religion, al-Khud champions the unity of the faithful, in practice, the umma is divided into several branches. By far the largest is called the Turathi. The Turathi affirm the umma's right in principle to select the successors of the Apostle (the Caliph), They also lack a formal priesthood that claims to mediate between the faithful and God - Turathi leaders are the judges, rulers, and pious mystics. The Turathi believe in the approaching Divine Judgment, but many don't live their life with particular urgency. The Turathi also prohibit the display of God or the Apostle - a practice they regard as idolatrous. Consequently, in their art, they use geometric, not representational, imagery. Among other notable practices of the Turathi are polygamy, and a prohibition on the consumption of pork and alcohol (though many among the elite observe this prohibition more in the breach).

The second most significant branch is called the Nasabi. The adherents of this branch accept the same basic tenets of al-Khud as do the Turathi, but they believe that that the leadership of the umma should be exercised by the direct descendants of the Apostle. For some of the Nasabi, the line of succession continues, but for others, it stopped with a particular imam, who has gone into hiding until the coming of the Divine Judgment. This imam is the Mahdi which is being expected in return at the appointed time. The Nasabi call for the overthrow of the existing political order to make way for the Mahdi. They control several of the key kingdoms of the Middle World, and call for others living in Turathi lands to join them. This makes them appealing to revolutionaries across the Middle World. But it also has made their leaders into something much more closely resembling a priestly caste.

There are also substantial groups of people professing other faiths living among the Khudi. One, called the Alfari, regard an earlier prophet named Gaal as having been divine, and having risen up after his death. The Khudi don't accept Gaal as anything more than a prophet, but they do agree with the Alfari that Gaal does return during the time of the Divine Judgment. An even older group called the Tabuti, claim that they were God's chosen, and their own Divine Revelation was complete and final. The Majus, for their part, believe that rather than God being omnipotent, he is opposed by a dark being of equal power, and conflict between them is ongoing. Although the Khudi don't accept these claims, they do regard all of the above as legitimate recipients of revelation, though distorted through human (and jinn) activity. For this reason, so long as they accept the political dominance of the Khudi and pay the poll tax, they are left to their own devices, and their own law. In contradistinction to some neighboring lands, religious minorities typically may live among the Khudi, and are not segregated in specific quarters. They do have to wear particular clothes or colors that identify them as adherents to their religion.

Aside from these, there are small mystical sects scattered across the Middle World. In remote areas, there may be isolated tribes that maintain ignorant beliefs in multiple gods (and it is said that before the birth of al-Khud, al-Wakim was numbered as merely one god among many).

A Land of Contrasts

The Middle World is laid out roughly as an east-west belt. It is watered by several mighty rivers that some say have their sources in Paradise. The rich alluvial land is able to support substantial populations. Along these rivers, cities sprang up long ago, and since those days, they have remained among the largest cities in the entire world. As al-Alam al-Wasat has access to all Seven Seas, its denizens can also boast of some of the world's largest ports, which control far-flung maritime trade routes. Coastal areas are likewise fertile, with grapes, olives and citrus fruits growing growing upon the slopes of coastal hills. In more remote areas, oasis towns also offer opportunities for wealth for those engaged in overland caravan trade.

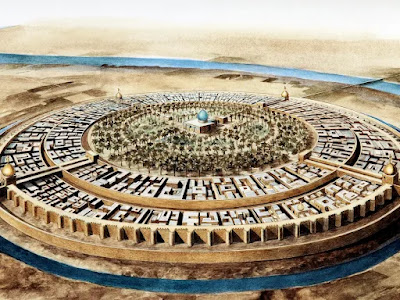

A Khud city is typically centered by a central House of Prostration, which abuts the city's main court - its legal heart, and the souk - its economic heart. A main street - the qasaba - runs through the center of the city, and contains its most important shops. Along the qasaba lie trade-specific or residential neighborhoods called mahallas. Most are organized around a central courtyard, which provides privacy to its residents. The city grows organically around these neighborhoods, connecting them by small lanes and alleys that facilitate human and camel, rather than vehicular, traffic. Aside from such neighborhoods, a large city contains numerous gardens, fountains, public baths called hamams, madrasah schools, hospitals and other charitable foundations, and caravanserais. In an elevated part of the city, one finds a walled compound containing the palace, and associated gardens. The entire city is defended by 20-foot walls (at a minimum). Most large cities in the Caliphate will contain 100,000 or more people, with the largest of them reaching a size of a half million or more.

|

| An idealized vision of the Virtuous City |

Beyond the river valleys and oases, and inland from the coast lie the badlands - deserts, mountains, and boundless steppes. Life is difficult here, but the badlands are not uninhabited. A variety of bedouins, mountaineers, and horse lords inhabit such areas. Many trade routes pass through their territory, but the caravans can only proceed at the sufferance of these folk, who also grow wealthy from the trade.

Perhaps the most important division is not the one between the Khudi and all the rest, but the one between the city dwellers (hadhari) and the nomads (badawi). The hadhari enjoy the bounties of civilization, and reap the advantages of living at the world's crossroads. However, centuries of soft urban living makes people soft and disparate. The badawi, conversely, have a strong sense of tribal solidarity, which allows them to act bravely and with a common purpose. Some sages have pointed out that this solidarity - asabiyyah - is the secret that allows al-Khud to renew itself by drawing new groups of nomads into its orbit. The new converts, driven by zeal, then expand the boundaries of the Domain of Khud. If this is the Divine Providence that will stave off destruction of those who have succumbed to prideful smugness remains to be seen. But unit the Day of Judgment, for as long as the House of Khud persists, so will the Domain of War - Dar al-Harb - beyond its borders.

Politics, titles and hierarchy

Though theoretically united as one Caliphate, the Middle World is divided into a number of distinct polities. The Caliph in Shahrinoor is accepted as the legitimate successor of the Apostle (by the Turathi), but in practice, he wields only symbolic power. Confined in his palatial paradise, he is regarded as not approachable by common mortals. De facto rule in the East is held by the Barys Sultan - a descendant of the Kushti - the Caliphate's nomadic slave soldiers from the northern steppes who have sidelined their previous masters. The Barys Sultan rules from the city of Resim. While the Kushti remain the most fearsome warriors in the Middle World, cities under their control are famed for their beauty, their poetry, and the activities of their sages.

|

| The Caliph's entourage |

In the center, the dominant power is the Zahir Sultan, who rules from the capital city Istiada in the ancient land of Myr. The Zahir Sultan is the richest ruler in the whole of the Middle World. The river Hakwah is the most fertile in the world, and Istiada's position in the center of the ecumene gives it a very advantageous position at the intersection of multiple overland and maritime trade routes. About a century ago, the founders of the Sultanate came close to reuniting the whole of the Middle World, beating back the challenges from both the Nasabi and the Fargun. But they too have begun to succumb to urban life, and power in the Sultanate increasingly resides in the hands of slave soldiers that also trace their lineage to the Kushti.

In the Far West, the strongest potentate is the Amir of Qarthayam, who rules over lands collectively called Imlaqiyyah. Furthest away from other Khudi centers, Imlaqiyyah is somewhat more insulated from the power games at the center. Their cities are cultural hubs no less than those ruled by the Barys Sultan, but their artisans, poets and scholars are more free to experiment with styles and methods. The cities of the West are somewhat pressed by the Fargun, who regard these lands as rightfully theirs.

Along the borders between the big empires, and on the margins the Middle World, some regions and cities enjoy de facto independence from any of major rulers. The are typically led by their own amir, though on occasion they are ruled by commercial oligarchies. This is true in the islands and coastal areas of the Bahr al-Fayruz, as well as oasis cities located along the Way of Silk. The site of the Salb, housing al-Khud's holiest shrine, is also self-ruled, though the Zahir Sultan is counted its protector.

The rulers of large empires typically call themselves 'sultan', or 'amir' (the latter title is also used by rulers of smaller polities as well). Some rulers have also claimed to be caliph, challenging the one in Shahrinoor. In Tat areas, kings call themselves 'shah'. Warlords among the Kushti who do not claim royal status call themselves 'beg', while those who do (and these typically live beyond the bounds of the Dar-al-Khud), call themselves 'khan' or 'khaghan'.

Rulers of polities typically have a council or cabinet of top advisors called a 'diwan'. The diwan is composed of viziers. The Chief or Grand Vizier - the Wazir al-A'zam or Wazir al-Kabir, is effectively a prime minister, and the second most-powerful (and in some cases, the de facto most powerful) person in the realm. Sometimes, when an empire is composed of distinct countries with a clear identity and history, there will be a Grand Vizier for each of these lands. The other members of the diwan are also called vizier - for instance, the Wazir al-Kharaj - the Minister of the Treasury, or the Wazir al-Jaysh - the Minister of the Army. Additionally, governors of specific provinces or cities that are appointed by the supreme ruler are also referred to as viziers. In some instances, these officials are called hakim - 'wise one'. It should be noted that jinn rulers in the Alam al-Ghayb are also counseled by viziers. The rulers (or occasionally, their governors) also appoint the judges (qadi) who make legal rulings, and the juridical scholars (mufti), who render authoritative opinions on the law. Rulers of some realms have a Grand Mufti.

Tribal groups are typically led by a sheikh, who exercises customary authority within their group. They are selected based on lineage, acclamation, or occasionally, fame, wisdom, or wealth. According to legal theorists, customary law has standing alongside formal, codified Khudi law (shari'a). In remote areas, tribes have a high degree of autonomy to govern themselves according to customary law (the situation is roughly similar in the case of religious minorities). It should be noted that other authority figures are sometimes referred to as 'sheikhs' - important scholars and heads of scholarly institutions, House of Prostration leaders, leaders of groups of mystics, and in smaller realms, the actual rulers themselves.

If a random table for determining a character's social class is desired, the following may be used:

06 - 15 Slave, servant

16 - 70 Peasant (fellah)

71 - 83 Artisan

84 - 89 Merchant

94 - 97 Scholar, religious official, administrator

98 - 00 Noble (Amir, Sheikh), etc.

Among the Khudi elite, roughly 35% have full ownership of land, whereas the rest hold their estate as a source of support in exchange for service granted by the state.

Among the peasants (fellahin), roughly 40% possess their own land, while the rest are sharecroppers who have a contract to work on land owned by others. It is also important to note that those who belonged to religious minority groups could own land, though their ownership was often subject to stricter regulations (limitations on size of estate, higher taxation, whether the land could be productive, etc.).

Slaves may be captured in war, or they may be criminals who have forfeited their freedom (or failed to repay debts). However, otherwise, the law prohibits Khudi to enslave other Khudi, and the Faith encourages the Faithful to free their slaves whenever possible.

Calendar

The Khudi calendar, introduced by the Apostle himself, has its roots in the calendrical system of the heathen Thani in the Age of Ignorance. It is a lunar calendar, where 12 lunar cycles constitutes a full year. Year 1 of this calendar marks the Exodus of Baha and his followers from Salb, and the establishment of the Caliphate in the city of Fadhila.

Each new month begins when a new crescent moon is first sighted. This makes the beginning of each month easily perceptible to the naked eye, though sages do perform calculations that predict the precise time of the start of each month. A month lasts 29 or 30 days, depending on the lunar cycle. 12 such lunar cycles constitute a typical Khudi year, which measures 354 days - considerably shorter than the solar year used by some of the Caliphate's neighbors. There is a 30-year cycle, in which a "leap year", when an extra day is added to the 12th month of the year on years 2, 5, 7, 10, 13, 16, 18, 21, 24, 26, and 29, occurs. Thus, on 11 out of the 30 years, the Khudi year is 355 days long.

The purpose of using a lunar calendar is so that celebrations and fasts, which are keyed into the lunar cycle, occur at the appointed time. The most important of these is the month of Shaghaf, which commemorates the first Revelation given to Baha. It is a month of fasting, which is punctuated by nightly celebrations. In addition, as al-Wakim is a transcendent God, the Khudi calendar disassociates key events and celebrations from the seasonal cycle of the solar year, which is a primary method of keeping heathen practices alive in a monotheistic society. Some detractors of the Khudi claim that the lunar calendar is actually a legacy of the Nashuraya - an ancient people who worshiped heavenly bodies - the moon first and foremost. The Nashuraya are recognized as recipients of revelation, and are therefore tolerated, though their influence on the Khudi calendar is denied. Nevertheless, in some quarters, the crescent moon has become a symbol of al-Khud.

|

| Counting the stars |

The Khudi week, like those of other revealed religions, numbers seven days. Their holy day, Shiyu, falls on the sixth day of the week, and is a day of collective prayer and rest from work. It is thus distinguished from the Tabuti and Alfari holy days, which fall on the last and first days of the week, respectively.

Coinage and the Economy

The lands of the Middle World use three main types of coins - the gold dinar, the silver dirhem, and the copper fals. Mints are operated by major and minor rulers alike, meaning that a multiplicity of coins circulate in Khudi lands. As a rule of thumb, however, coins weigh three to four grams, and the exchange value between the three types of coins tends to be fixed on the ratio of 1:10:500 (i.e. there are 10 dirhems to a dinar, and 50 fals to a dirhem). This means that prices largely approximate those of more standard settings, but items priced in copper will be five times dearer.

Most items from standard equipment lists will be available for purchase from any decent-sized souk or specialty shop. Additionally, buyers in al-Alam al-Wasat may purchase the following items:

Alnakh swords: steel produced in the smithies of the city of Alnakh is especially strong, and blades manufactured from it are exceptionally sharp. Alnakh blades (typically sabres or scimitars) are effectively +1 weapons, and save with advantage against breaking. They are not considered magical weapons, however. Cost: 150 dinars+.

Incense: Frankincense, myrrh oil. Cost: 2 dinars/lb. for the former, 10 dinars/lb. for the latter. The use of these substances yields clearer visions for divination spells (e.g. Augury provides a vision, rather than simply an answer to a yes/no question. Hashish pellets, which can have a similar effect can also be acquired for 10 dinars each. A standard pellet will cause the eater to save at disadvantage against enchantment spells. Note that these are not smoked, but mixed with honey and ingested.

Papyrus sheet: allows to add double proficiency for copying spells. Price: 5 dirhems (in the land of Myr, 2 dirhems).

Silk caftan: aside from the beauty of the material, silk garments reduce all piercing damage against the wearer by 1 per die. Cost: 65 dinars+.

Tat carpets: 100 dinars+. May be enchanted, to obvious effect.

|

| The Middle World - a land of plenty |

Finance is also quite well-developed in the Middle World. One is able to receive a letter of credit, which can be used at any establishment that belongs to a family business network in another city.

No comments:

Post a Comment